Maria couldn’t sleep. For three months, her neighbor’s backyard had been buzzing with construction crews installing what looked like a massive concrete bunker. The city council meeting had been heated – something about “temporary nuclear waste storage” for a research project. Half the neighborhood wanted to move away immediately.

What Maria didn’t know was that her sleepless nights were connected to a breakthrough that could change how the world thinks about both nuclear waste and clean energy. That concrete structure wasn’t just storing radioactive material – it was slowly transforming it into something incredibly valuable.

The engineers working inside that facility weren’t just managing waste. They were essentially performing nuclear alchemy, turning society’s most feared byproduct into the fuel that could power humanity’s energy future.

The Breakthrough That Nobody Saw Coming

Nuclear waste tritium production represents one of the most counterintuitive solutions in modern science. For decades, we’ve treated nuclear waste like toxic trash that needs to be buried and forgotten. Meanwhile, fusion energy projects worldwide have been desperately searching for tritium, the rare hydrogen isotope that makes fusion reactions possible.

- Scientists discover 60 million Antarctic fish nests under ice, then everything goes horribly wrong

- Scientists discover this kitchen herb works better than store-bought air fresheners for odor elimination

- Japanese company plans massive luna ring of solar panels around Moon’s equator by 2035

- The hidden psychology behind excessive politeness reveals 7 alarming signs you never noticed

- Marine authorities consider stunning orcas to stop yacht attacks, sparking massive backlash from conservationists

- Rats ate London’s internet cables and killed a £300 million rescue deal

American researchers and startups have figured out how to kill two birds with one stone. They’re using controlled neutron bombardment to transform long-lived radioactive waste into tritium – essentially converting our biggest nuclear headache into fusion energy’s most precious ingredient.

“We’re not just managing waste anymore,” explains Dr. James Chen, a nuclear engineer working on waste-to-tritium systems. “We’re mining it for the building blocks of clean energy.”

The process works by placing nuclear waste in specially designed reactors where neutrons interact with specific isotopes. Through carefully controlled nuclear reactions, some waste materials transform into tritium, which can then be extracted and purified for use in fusion reactors.

The Numbers Game: Why Every Gram Matters

The scale of the tritium shortage is staggering. Current global production barely meets research needs, let alone commercial fusion requirements. Here’s what the nuclear waste tritium landscape looks like:

| Source | Annual Tritium Production | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian CANDU Reactors | 1.5-2 kg | Declining capacity |

| U.S. Military Production | Limited quantities | Classified/restricted |

| Waste-to-Tritium Projects | 50-200 grams | Rapidly scaling |

| Future Fusion Demand | 50+ kg annually | Required by 2040 |

Even small amounts of tritium carry enormous value. Current market prices hover around $30,000 per gram, making tritium more expensive than diamonds. For fusion companies racing toward commercial viability, securing a steady tritium supply often determines their entire business strategy.

The waste-to-tritium approach offers several advantages:

- Reduces long-term nuclear waste storage requirements

- Creates valuable fuel from unwanted material

- Provides domestic tritium production capability

- Generates revenue from waste management operations

“Every gram of tritium we produce from waste is a gram we don’t have to import or manufacture through other expensive methods,” notes Sarah Rodriguez, a policy analyst specializing in fusion energy economics.

Real-World Impact: Who Benefits and Who Worries

The implications of successful nuclear waste tritium production extend far beyond laboratory walls. Communities near nuclear facilities could see their biggest liability transformed into an economic asset. Instead of paying billions for long-term waste storage, utilities might actually profit from their radioactive inventory.

Fusion energy companies stand to benefit most directly. Private firms like Commonwealth Fusion Systems and Helion Energy have raised billions in funding, but their success hinges on securing adequate tritium supplies. Domestic production from waste could accelerate fusion development by decades.

However, not everyone is celebrating. Environmental groups worry about increased nuclear waste transportation and handling. Local communities fear that waste-to-tritium facilities could become permanent fixtures rather than temporary solutions.

“We support fusion energy, but we need guarantees that this doesn’t just create new reasons to keep nuclear waste in our neighborhoods forever,” says Michael Torres, a community activist in Colorado.

The technology also raises geopolitical questions. Countries with large nuclear waste inventories suddenly possess potential fusion fuel stockpiles. Nations without significant nuclear programs might find themselves at a disadvantage in the clean energy transition.

International energy markets are already responding. Tritium futures contracts have appeared on commodity exchanges, and several countries are fast-tracking waste-to-tritium research programs.

The Technical Challenge: Making It Work at Scale

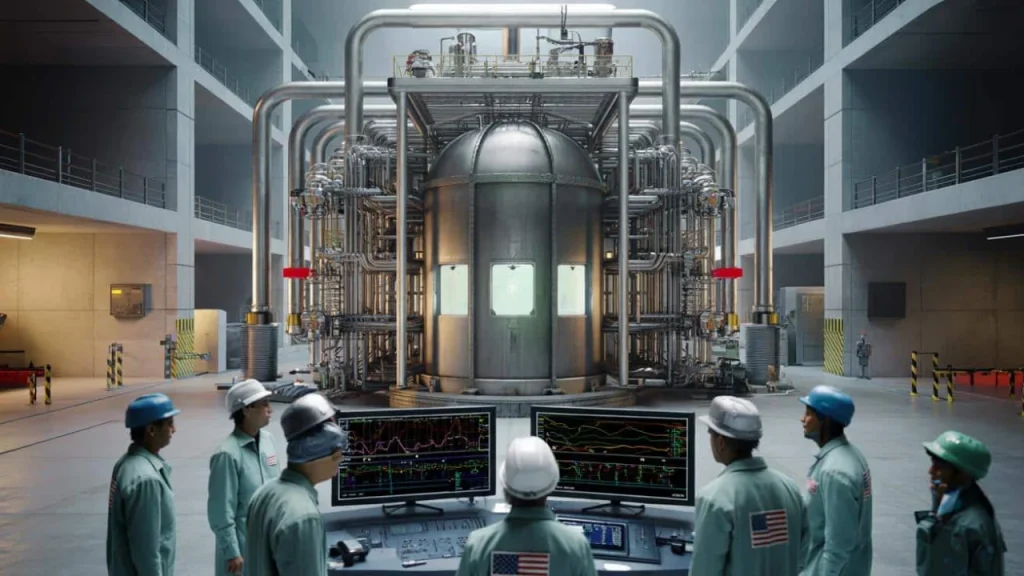

Current waste-to-tritium systems operate more like precision laboratories than industrial facilities. Engineers must carefully balance neutron bombardment to maximize tritium production while minimizing unwanted reactions that could create different radioactive isotopes.

The extraction process requires sophisticated separation technologies. Tritium must be isolated from complex waste mixtures containing dozens of different radioactive elements. Even tiny contamination levels can render tritium unusable for fusion applications.

Safety systems add another layer of complexity. Unlike traditional waste storage, active tritium production involves handling both input waste and valuable output materials. Facilities need redundant containment systems and real-time monitoring of both radioactivity and tritium concentrations.

“The engineering challenge isn’t just making tritium from waste,” explains Dr. Chen. “It’s doing it safely, consistently, and at a cost that makes economic sense for fusion energy.”

Scaling up presents additional hurdles. Current demonstration systems process kilograms of waste to produce grams of tritium. Commercial fusion reactors will need steady supplies measured in kilograms, requiring much larger processing facilities.

FAQs

Is nuclear waste tritium production actually safe for communities?

Current facilities use multiple containment systems and operate under strict regulatory oversight, though long-term safety depends on proper facility management and waste handling protocols.

How much tritium can realistically be produced from existing nuclear waste?

Early estimates suggest existing U.S. waste inventories could yield several hundred kilograms of tritium over decades, potentially meeting early commercial fusion demands.

Will this technology make nuclear waste disappear?

No, waste-to-tritium processes only convert small portions of waste into tritium while reducing overall radioactivity levels and storage timeframes.

When could waste-to-tritium facilities become commercially operational?

First commercial-scale facilities could begin operations within 5-7 years, coinciding with the expected timeline for commercial fusion reactor deployment.

Could this technology be used by countries to develop nuclear weapons?

While tritium has weapons applications, waste-to-tritium facilities operate under international monitoring and produce quantities primarily suitable for civilian fusion energy programs.

What happens to nuclear waste that doesn’t become tritium?

The remaining waste typically has reduced radioactivity and shorter decay periods, making long-term storage more manageable and less expensive.