Marie-Claire had always loved bringing her daughter to the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Paris. Every Saturday, they’d walk through the halls of scientific marvels, with eight-year-old Sophie pressing her nose against the glass cases. Last month, Sophie discovered Blaise Pascal’s calculating machine—the Pascaline—and spent twenty minutes asking how the brass wheels worked.

“Maman, how did people count before computers?” she’d asked, tracing the air above the delicate mechanisms. Marie-Claire tried to explain, but the machine itself told the story better than words ever could.

This week, when Marie-Claire called to book their usual Saturday visit, she learned something that made her stomach drop. That same Pascaline calculating machine—one of only a handful left in the world—had been sold at auction to a private collector. Sophie’s favorite exhibit was gone forever.

The Shock Heard Around Scientific Circles

The sale of the Pascaline calculating machine sent shockwaves through universities, museums, and research institutions across Europe. When the hammer fell at €2.3 million in a Parisian auction house, it wasn’t just another expensive antique changing hands—it was a piece of humanity’s scientific heritage disappearing into private ownership.

Dr. Elena Rodriguez, a historian of science at the Sorbonne, didn’t mince words: “This feels like watching the Mona Lisa being sold to decorate someone’s living room. The Pascaline isn’t just an artifact; it’s the DNA of every computer we use today.”

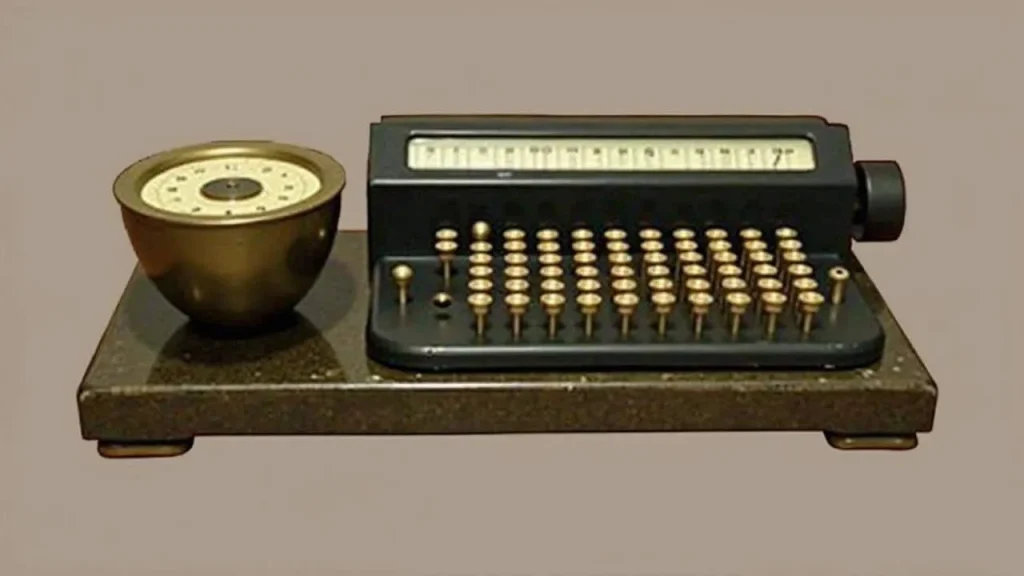

Designed by 19-year-old Blaise Pascal in Normandy around 1642, the Pascaline calculating machine was revolutionary. Pascal created it to help his father, a tax collector, handle the endless mathematical calculations required for his work. But what started as a family favor became the foundation of mechanical computation.

The machine’s brass wheels and intricate gear system could perform addition and subtraction automatically—a miracle in an age when most calculations required human hands, abacuses, or endless pen-and-paper arithmetic. Pascal built around 50 prototypes, constantly refining the mechanisms to handle the complex “carry” operations that made his machine truly functional.

What Makes the Pascaline So Revolutionary

Understanding why scientists are so upset requires looking at what made the Pascaline calculating machine special. This wasn’t just clever craftsmanship—it was a fundamental leap in how humans approached problem-solving.

The technical achievements of Pascal’s design were extraordinary for the 17th century:

- First mechanical calculator to handle automatic carrying between digits

- Precision brass gears that remained accurate despite repeated use

- Input and display systems that non-mathematicians could operate

- Modular design allowing for different number bases and operations

- Self-correcting mechanisms that prevented operator errors

Professor James Mitchell from Cambridge University explains it simply: “Pascal basically invented user-friendly computing 400 years ago. Every smartphone, every laptop, every digital device traces its conceptual lineage back to this machine.”

| Feature | Pascaline (1642) | Modern Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Automatic calculations | Addition/subtraction via wheels | Basis for all digital processors |

| Error prevention | Mechanical constraints | Software validation systems |

| User interface | Numbered dials and windows | All modern input/output design |

| Modular construction | Interchangeable components | Modern computer architecture |

But the Pascaline’s influence went beyond pure mechanics. It represented a philosophical shift—the idea that human intelligence could be enhanced, not replaced, by machines. Pascal wasn’t trying to make people obsolete; he wanted to free them from tedious calculations so they could focus on more complex thinking.

Why Scientists Feel This Sale Crosses a Line

The scientific community’s anger isn’t just about losing access to one machine. It’s about a pattern that’s been accelerating over the past decade, where irreplaceable historical artifacts disappear into private collections.

Dr. Sarah Chen, who runs the International Committee for Scientific Heritage, has tracked this trend: “We’ve lost seventeen major calculating devices to private sales in the last five years. These aren’t just museum pieces—they’re active research tools. Students need to see how these mechanisms work. Engineers need to understand the evolution of design thinking.”

The practical implications are immediate and far-reaching:

- Educational programs lose access to hands-on learning opportunities

- Researchers can’t study construction techniques or test historical theories

- Documentary filmmakers and science communicators lose visual resources

- Future generations may only see these machines in photographs

What particularly frustrates scientists is that public institutions simply can’t compete with private collectors. The €2.3 million final bid for this Pascaline calculating machine represents more than most university museums spend in a decade.

“We’re not asking people not to collect,” says Dr. Rodriguez. “We’re asking them to consider loan programs, partnerships, or donations that keep these treasures accessible to everyone.”

The Ripple Effects Nobody Talks About

Beyond the immediate loss of the machine itself, this sale represents something deeper—a shift in how society values scientific heritage. When crucial artifacts become luxury commodities, it changes how we think about shared human knowledge.

Teachers are already feeling the impact. Laurent Dubois, who runs STEM programs for Paris schools, had planned field trips around seeing the Pascaline: “You can show kids pictures all day, but when they see those brass wheels turn, when they understand that a teenager figured this out centuries ago—that’s when science becomes real for them.”

The timing makes it worse. Just as educators are fighting to make STEM subjects more engaging and accessible, key teaching tools are disappearing behind closed doors. Museums report that interactive historical exhibits consistently rank among their most popular attractions, especially for younger visitors.

Research communities are also concerned about precedent. If the Pascaline calculating machine can be sold without public outcry, what’s next? Early telescopes? Original manuscripts from Newton or Galileo? Historical scientific instruments that represent centuries of human curiosity and ingenuity?

Dr. Mitchell puts it bluntly: “We’re essentially allowing the privatization of human intellectual history. Future historians may have to knock on rich people’s doors to study the tools that built our modern world.”

What This Means for Science Education

The loss of the Pascaline affects more than just researchers and museum curators. Science education depends on students being able to connect abstract concepts to real, tangible objects that they can see and touch.

Studies consistently show that students learn better when they can examine historical scientific instruments firsthand. The Pascaline calculating machine was perfect for this—complex enough to be impressive, simple enough to understand, and directly connected to technology students use every day.

Now that connection is broken. Instead of seeing Pascal’s actual gears and mechanisms, students will have to settle for replicas, videos, or imagination. The authenticity that made the machine so powerful as a teaching tool is gone.

This creates a broader problem for scientific literacy. If young people can’t see the historical progression of human ingenuity, how do they understand that science isn’t magic—it’s a long chain of curious people building on each other’s work?

FAQs

What exactly is the Pascaline calculating machine?

It’s the first successful mechanical calculator, invented by Blaise Pascal in 1642 when he was just 19 years old. The brass and steel device could automatically perform addition and subtraction using a system of gears and wheels.

Why are scientists so upset about this sale?

They believe historical scientific instruments belong in public institutions where researchers and students can study them. Once sold to private collectors, these irreplaceable artifacts often disappear from public access permanently.

How much did the Pascaline sell for?

The machine sold for €2.3 million at a Paris auction house, far more than most public museums could afford to bid.

How many original Pascalines still exist?

Only about 20 original Pascaline calculating machines survive today, making each one extremely rare and historically significant.

Could this sale have been prevented?

Some scientists argue for stronger cultural heritage protection laws that would require offering such artifacts to public institutions before private sale, similar to systems used in other countries.

What makes the Pascaline so important to computer history?

It established fundamental principles of mechanical computation that directly influenced every calculating device developed afterward, from mechanical calculators to modern computers and smartphones.