Sarah watched her 16-year-old daughter Emma scroll through her phone while she spoke about upcoming exams. “Emma, did you hear what I just said about your chemistry test?” she asked for the third time. Emma looked up with that familiar glazed expression and mumbled, “Yeah, mom, I heard you.”

But Sarah knew better. Within hours, Emma would be frantically texting friends about the very same test her mother had just mentioned. It was like talking to a wall, except the wall occasionally rolled its eyes.

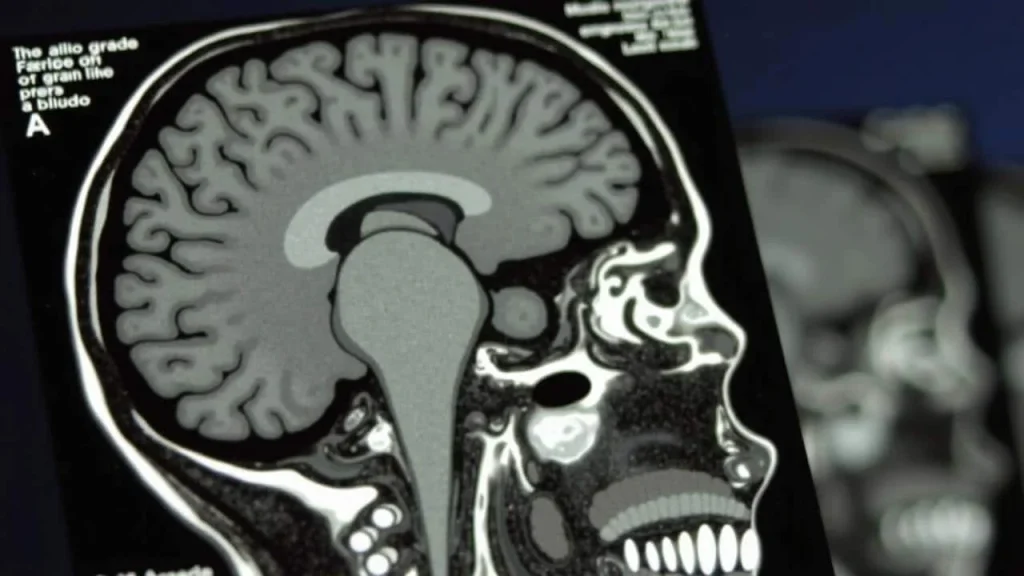

What Sarah didn’t know was that her daughter’s brain was literally programmed to tune her out. Recent MRI research has revealed something that might make every frustrated parent feel a little better about those eye-rolling moments.

Your Teen’s Brain Actually Rewires to Ignore You

Scientists at Stanford University and other research centers have been scanning teenage brains to understand why adolescents seem to develop selective hearing when it comes to their parents. What they discovered through MRI technology explains years of family dinner frustrations.

The research shows that teenage brain development includes a dramatic shift in how adolescents process familiar versus unfamiliar voices. When researchers played recordings of mothers’ voices to teenagers in MRI scanners, something remarkable happened.

“We found that the teenage brain shows decreased activation in reward and attention areas when hearing their mother’s voice, compared to hearing unfamiliar voices,” explains Dr. Daniel Abrams, a neuroscientist who led one of the key studies.

Before puberty, a mother’s voice lights up multiple brain regions associated with reward, emotion, and attention. But around age 13-14, that pattern flips completely. The same voice that once commanded immediate attention becomes background noise.

Meanwhile, when teenagers heard voices of strangers or other teens, their brains suddenly became highly engaged. Reward circuits activated, attention networks sharpened, and social processing areas began working overtime.

The Science Behind Teenage Selective Hearing

The MRI findings reveal specific patterns in teenage brain development that explain this phenomenon:

- Reward system changes: The nucleus accumbens, which processes rewards, shows decreased activity when hearing parental voices

- Attention networks shift: Areas responsible for focused attention become less responsive to familiar family voices

- Social brain activation: Regions processing social relevance become hyperactive when hearing peer voices

- Identity formation areas: Brain regions linked to self-identity and independence show increased resistance patterns

This neurological shift appears to be evolutionarily programmed. Adolescents need to develop independence and form connections outside their family unit to survive as adults.

| Age Group | Mother’s Voice Response | Stranger’s Voice Response |

|---|---|---|

| 7-12 years | High reward activation | Moderate interest |

| 13-16 years | Significantly decreased | Enhanced attention |

| 17+ years | Gradual recovery | Balanced processing |

“The teenage brain is essentially preparing them to leave the nest,” says Dr. Eva Telzer, a developmental neuroscientist. “This isn’t defiance – it’s biology doing exactly what it’s supposed to do.”

What This Means for Families Everywhere

Understanding the neurological basis of teenage behavior changes everything about how parents can approach communication with their adolescents.

The research suggests that teenagers aren’t deliberately ignoring their parents out of disrespect. Their brains are literally wired to pay more attention to voices outside their family circle. This biological shift helps explain why teens often seem more influenced by friends, teachers, or even strangers than by their own parents.

Dr. Abrams notes, “Parents often feel hurt when their teenager seems to value everyone else’s opinion more than theirs. But this research shows it’s not personal – it’s developmental.”

The implications extend beyond family dynamics. This research helps explain why peer influence becomes so powerful during adolescence. When a teenager’s brain is programmed to find unfamiliar voices more rewarding and attention-grabbing, peer pressure takes on new meaning.

However, the news isn’t all discouraging for parents. The brain imaging also revealed that while teenagers might tune out direct parental advice, they still process emotional tone and underlying care. The parent-child bond remains strong even when the communication channels seem blocked.

Some practical strategies emerge from this research:

- Use indirect communication: Information delivered through other trusted adults may be more effective

- Focus on emotional connection: Maintaining warmth and support matters more than getting immediate compliance

- Leverage peer influence positively: Encourage relationships with peers who share your family’s values

- Be patient with the process: The brain patterns gradually shift back toward balance in late adolescence

“Understanding that this is a normal part of teenage brain development can help parents take the behavior less personally,” explains Dr. Telzer. “Your teenager still loves you – their brain is just programmed to listen to the world beyond your voice right now.”

Looking Beyond the Teenage Years

The research also provides hope for parents weathering these challenging years. Brain scans of older teenagers and young adults show that the extreme bias against parental voices gradually diminishes.

By the late teens and early twenties, young people begin to process familiar and unfamiliar voices more equally. The parent-child relationship can evolve into something more balanced and reciprocal.

This research represents a significant breakthrough in understanding adolescent behavior through the lens of neuroscience. Rather than viewing teenage behavior as purely psychological or social, we can now see the biological foundations that drive these patterns.

For millions of parents currently navigating the teenage years, this research offers both explanation and reassurance. Those eye-rolls and selective hearing episodes aren’t signs of failure in parenting – they’re signs that teenage brain development is proceeding exactly as nature intended.

FAQs

At what age does the teenage brain start tuning out parents?

The shift typically begins around age 13-14, coinciding with the onset of puberty and major brain development changes.

Do teenagers eventually start listening to their parents again?

Yes, brain scans show that the bias against parental voices gradually decreases in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Is this selective hearing the same for both mothers and fathers?

Most studies have focused on maternal voices, but research suggests similar patterns occur with paternal voices and other primary caregivers.

Can parents do anything to improve communication during this phase?

Yes, focusing on emotional connection, using indirect communication through trusted adults, and understanding this as normal development can help.

Does this brain pattern affect all teenagers equally?

While the general pattern is consistent, individual differences exist based on personality, family dynamics, and other developmental factors.

Is this teenage brain development pattern found across different cultures?

Research indicates this appears to be a universal aspect of human adolescent brain development, though cultural factors may influence its expression.